The Cultural Life of the World Cup

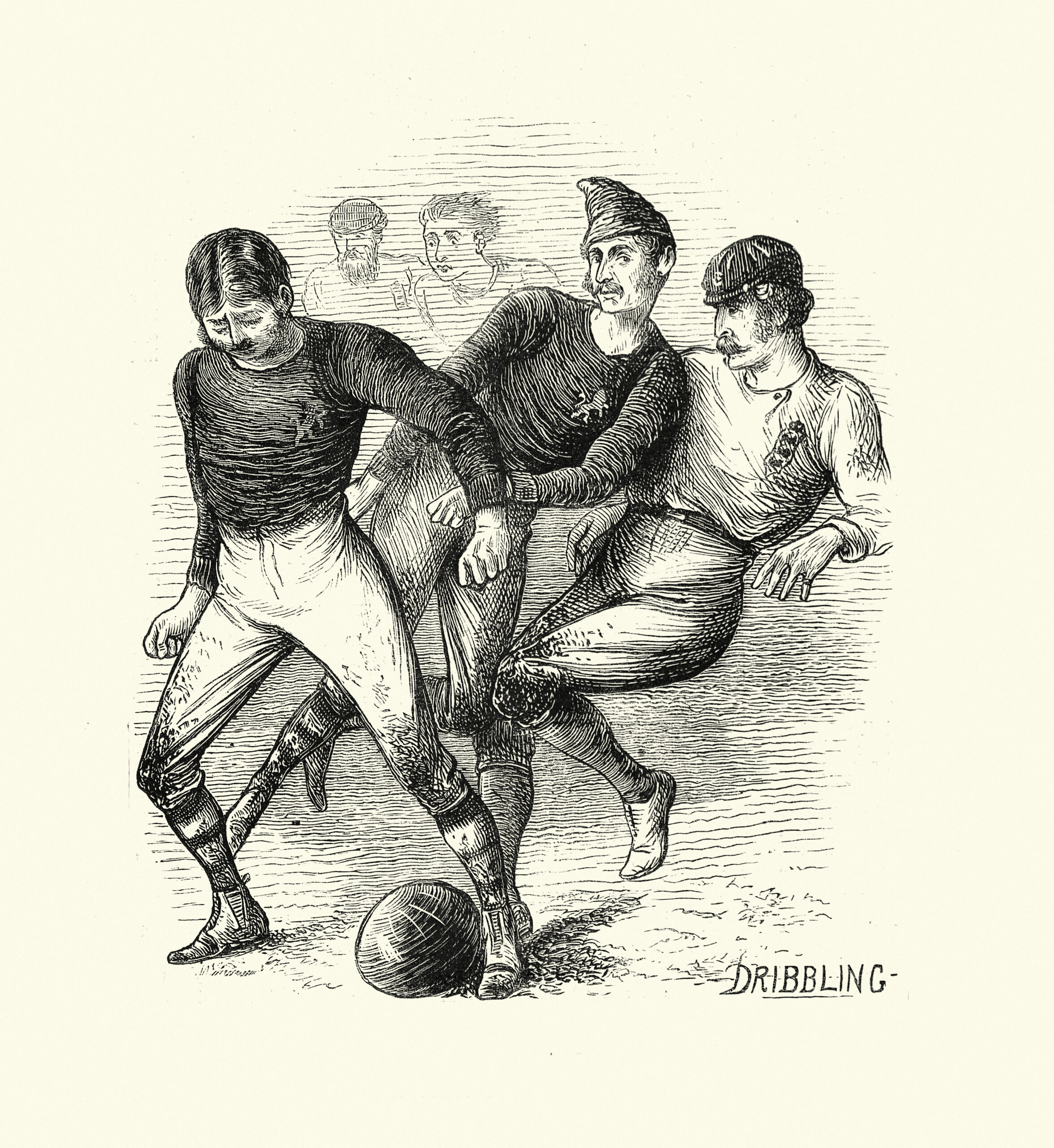

IMAGE LEFT: An original newspaper illustration depicting the first-ever international soccer match, played between Scotland and England in 1872, marking the beginning of global tournaments.

As the FIFA World Cup 2026 approaches, sixteen host cities across Canada, the United States, and Mexico are gearing up for a tournament that reaches far beyond the stadiums. From June 11 to July 19, 2026, North America will enter a period of shared cultural exchange, welcoming people from around the world. Here in New York City, matches at MetLife Stadium, including the final, are just one part of the story. Alongside them, a broader shift is felt across daily life, shaping how we gather, celebrate, and communicate.

For nearly a century, FIFA has treated the World Cup not only as a sporting event but also as a cultural platform, working with artists and designers to shape how the tournament is seen and experienced beyond the game. Because creative thinking sits at the heart of The Fifth’s identity, this moment invites a closer look at how the World Cup has influenced art, design, and visual culture across time and place. What follows are a few examples of how that influence has taken shape.

Designing Identity

Official World Cup Posters, from Italia ’90 to 2026

Large international events walk a fine line. They need to feel unified, without flattening local identity. Since the first tournament in 1930, World Cup posters have served as graphic ambassadors, translating the character of host cities and countries into images meant for a global audience. Over time, these posters have reflected changes in politics, cultural values, and how each host wants to be perceived.

The posters created for the 1990 World Cup in Italy offer a clear example. Designed by Italian artist Alberto Burri, they combined references to ancient Rome with modern abstraction, grounding the tournament in Italy’s history while speaking in the visual language of the moment.

In 2026, that tradition continues with a series of official host city posters, each created by a different artist and shaped by the place it represents. Rather than presenting a single, unified look, the series reads as a set of distinct perspectives. Viewed together, the posters reflect the spirit of We Are 26, showing how many voices can share the same moment without needing to sound the same.

Framing the Moment

Annie Leibovitz’s Mexico ’86 World Cup Series

Photography helps shape how the World Cup is experienced and remembered. Beyond documenting matches, it can situate the tournament within a broader cultural and historical context.

For the 1986 World Cup in Mexico, Annie Leibovitz was commissioned to create a series of promotional images for the tournament. Rather than focusing solely on action, she approached the project as a portrait of place, developed over the course of a year through multiple journeys across Mexico. The resulting 13-poster World Cup Soccer Series brought together contemporary players, the ball, and human figures with Mexico’s ancient history, often set against archeological sites and other iconic natural landscapes.

The series drew international attention, presenting Mexico not only as a host nation but as a place with deep cultural continuity. These images expanded how audiences perceived the tournament, reminding viewers that sport gains meaning through where and how it is seen.

Design in Motion

Trionda, the Official Match Ball of the 2026 World Cup

Even the most functional elements of soccer reflect the same design-minded approach. Design shows up not only in imagery, but in the objects used again and again throughout the tournament.

The Official Match Ball for 2026, Trionda, created by adidas, sits where design meets play. The name draws from two ideas: “Tri,” for the tournament’s three host nations, and “onda,” meaning “wave” in Spanish, suggesting shared energy across North America. A red, green, and blue colorway and fluid geometry reinforce movement and unity, while a triangular form at the center nods to the partnership behind the tournament.

Symbolism does not override use. Deep seams give the ball its visible structure. Embossed textures shape the surface. The four-panel geometry defines both flight and appearance. The result is a ball that gives “keep your eye on the ball” a new meaning.

More Than a Game

Nike’s World Cup Campaigns

Over the years, Nike has used the World Cup as a platform for culturally driven storytelling. Drawing on music, youth culture, humor, and street style, the work connects past legends with new generations and shapes how soccer shows up in everyday life. The result is something understood instantly, without translation.

One of Nike’s most memorable examples was “Winner Stays.” Created in 2014 for the Brazil World Cup, this iconic campaign captured the energy of a pick-up game in which children tap into the abilities of their superstar heroes, such as Cristiano Ronaldo, Neymar, and Gerard Piqué. Playful and aspirational, it tapped into the simple fantasy at the heart of the sport: for a moment, anyone can be great.

What makes the work effective is how familiar it feels. Even without knowing the sport, the feeling comes through. The campaigns reflect how soccer already lives beyond the stadium.

Stadiums That Remain

Estadio Centenario in Montevideo, Uruguay

Some of the most lasting traces of the World Cup are architectural. Long after crowds have left, stadiums continue to shape how cities gather and remember.

The earliest example is the Estádio Centenario in Montevideo, built in just nine months for the inaugural 1930 World Cup. Constructed during Uruguay’s centenary celebrations, the stadium was designed as more than a place to watch a match. Its modernist form, anchored by a tall ceremonial tower known as the Torre de los Homenajes, became a monument, announcing soccer’s permanent place in public life.

Over time, it became a civic landmark, hosting national ceremonies and political gatherings alongside matches. In 1983, FIFA designated it the first Historical Monument of World Football, a reminder that architecture carries memory forward.

After the Crowds

When the final match is played on July 19 at MetLife Stadium, host cities across North America slowly return to their routines, but traces of the World Cup remain. It’s a familiar cycle, repeated every four years: posters saved, photographs resurfacing, objects marked by use, and buildings that continue to shape how people come together.

At The Fifth, we’re interested in noticing these small remnants, in how something global settles into everyday life. When the world comes to town, it leaves behind more than excitement. It leaves behind details worth paying attention to.

We’re excited to welcome the world to New York and to The Fifth.